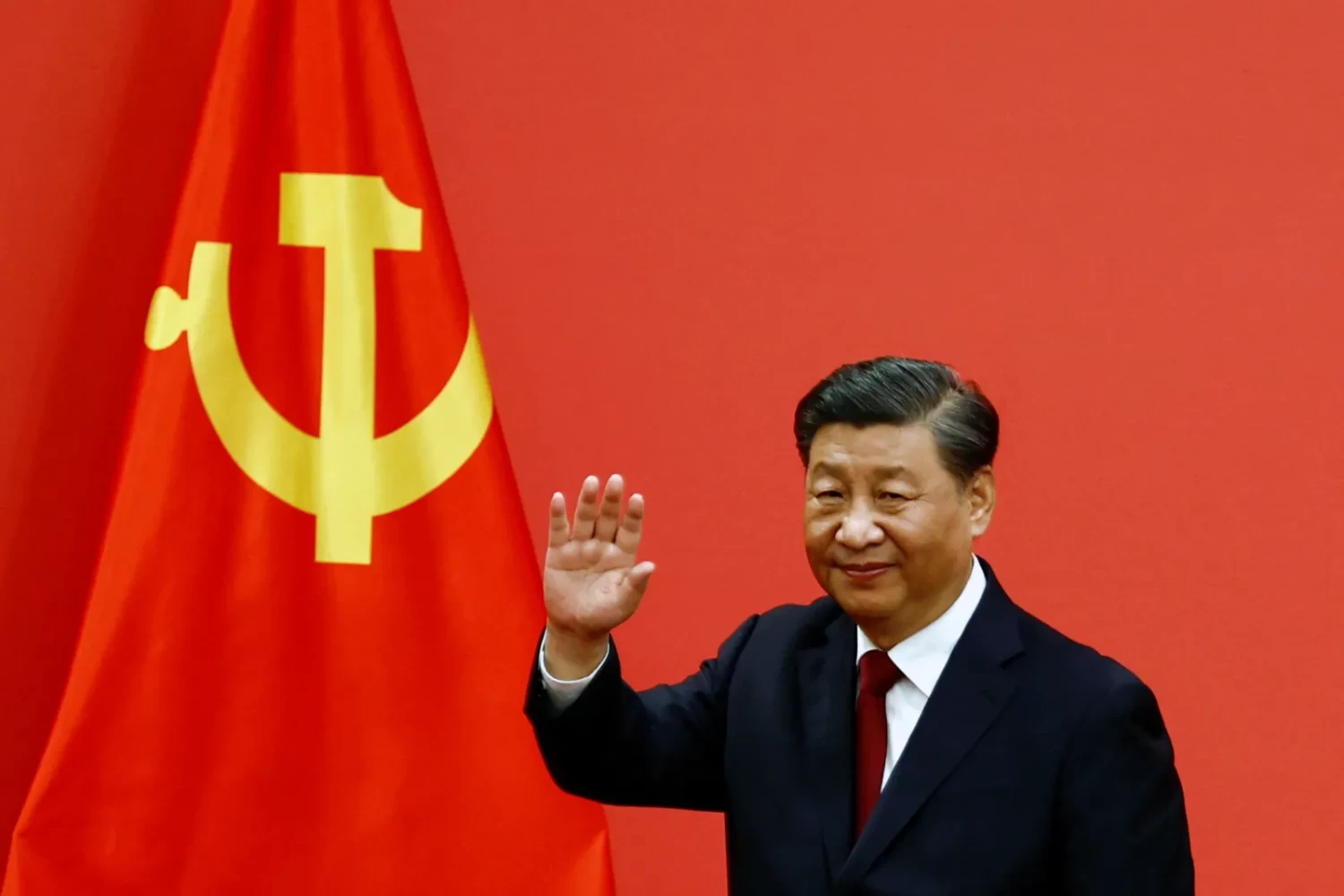

‘A nation at risk’: Has Chinese leader Xi Jinping bitten off more than he can chew?

|

China’s Chairman, Xi Jinping, stands on a precipice. An international backlash is growing against his assertive ambitions. His tightly controlled public are facing new economic uncertainty. It begs the question: Has China’s leader overreached? In January, Chairman Xi warned a short-notice session of the Communist Party that globally, “sources of turmoil and points of risk are multiplying.” “(At home) the party is at risk from indolence, incompetence and of becoming divorced from the public,” he said. Then there was “grey rhinos” and “black swans” — Chinese stock market jargon for bear-like economic conditions. Xi was right. Social unrest is being played out on the streets of Hong Kong. Economic growth has slowed. Debt is exploding. The trade war with the US keeps escalating. International outcry continues to swell around the South and East China Seas, and the plight of the Uighurs. Then there’s global push-back against state-influenced loans and companies such as Huawei. It’s a scenario leading many international analysts to wonder if Chairman Xi has overextended himself. Has he led China off a diplomatic and social precipice before being fully prepared? “[Many] would also think that he’s mishandled relations with the US by showing China’s hand too early and bringing on a conflict,” said Lowy Institute Senior Fellow, Richard McGregor. “This might have been inevitable — but Xi’s certainly brought it on by the way he’s behaved.”

BULL IN A CHINA SHOP While there are no immediate challengers to Chairman Xi prominent within the Chinese Communist Party, he is determined to prevent one from rising Any dissent will be extinguished, he warned in January, saying “younger officials must go in guns blazing to take on these major struggles.” Now that resolve is being put to the test. The secretary-general of the Chinese Communist Party’s law and order committee, Chen Yixin, has warned the power of social media meant even “a small incident can form into a vortex of public opinion.” “[We must] prevent social and economic risks evolving into political risks,” Chen Yixin added. In Hong Kong, that scenario has unfolded. Yet while Xi is yet to be the subject of a full-scale backlash, he is facing criticism for his authoritarian tendencies, Richard McGregor recently told a Lowy Institute podcast about his book , Xi Jinping: The Backlash . “What I’ve tried to describe in different ways, is his critics and his opponents at home — and the increasingly concerted and co-ordinated opposition abroad,” he said.

BACKLASH BEGINS China’s list of international “incidents” is growing at an alarming rate. It’s all because of Xi’s willingness to be assertive over his territorial, economic and cultural claims. Hong Kong may be Chinese territory. But it is caught between British-sponsored democracy and Chinese Communist Party control. The incompatibility of these two ideologies has resulted in the civil unrest seen there now. Meanwhile, Canada is in Beijing’s “black books” because of the arrest of Huawei’s chief financial officer (and daughter of its founder) Meng Wanzhou on charges of breaching international sanctions with Iran. Singapore, Germany and France have all revised their diplomatic stance with Beijing after high-profile disagreements. South Korea has been threatened with sanctions over accepting US THAAD anti-missile defences. Sri Lanka has discovered the true price of debts with Beijing. And Australia, amid ongoing scandals of political interference, has barred the high-profile Chinese tech firm Huawei from involvement in the 5G communications rollout. Amid it all, the trade dispute between China and the United States continues to escalate into a trade war. “There’s no agreement on how to handle China, to push back against China,” McGregor said. “But there are more conversations, particularly among democracies, than there ever has been.” “There is good reason to think, as many Chinese officials and scholars do, that Xi’s overreach will come back to haunt him before the next party congress, in late 2022, especially if the Chinese economy struggles,” McGregor said “By then, potential rivals might be willing to risk making their ambitions public.”

UNCOMPROMISING LEADER Xi remains an enigma. Both to the world and his people. “As misguided as many foreigners might have been, even Xi’s colleagues don’t appear to have known what they were getting when, in 2007, they tapped him to take over,” McGregor wrote in Foreign Affairs. “There was no sense in 2007 that party leaders had deliberately chosen a new strongman to whip the country into shape. The compromise candidate would turn out to be a most uncompromising leader.” Where once there was a distinction between the Chinese Communist Party and the mechanics of government, there is no more. Where his predecessors had attempted to professionalise government by taking politics out of it, Chairman Xi has sought to reimpose central party control. “If Xi believes in anything, it’s in the absolute centrality of party power,” McGregor writes. “Only the party has the right to run China. Only the party can run China. And if you think of it like that, you start to get a better explanation for Xi’s actions.” Religious affairs, media and entertainment, private enterprise and similar public policy areas have come under party committee control.

While looking in on China’s strictly censored social and state-controlled media shows little sign of it, conditions are ripe for dissent. “There are many people in China who were once very powerful, and who would love to see Xi Jinping fall flat on his face,” McGregor told the Lowy Institute. “The technocratic elite, the people, the scholars and the like … dislike Xi Jinping intensely for the way he’s wound back human rights, legal reform in particular — and by appointing himself president in perpetuity.” TROUBLED TIMES Chairman Xi’s behaviour, McGregor said, also appears guided by fear. He’s convinced his colleagues are working against him. He has cause to believe so. “Xi has displayed remarkable boldness and agility in bending the vast, sprawling party system to his will,” McGregor says. “Sooner or later, however, as recent Chinese history has shown, the system will catch up with him. It is only a question of when.” Xi’s ambitions were such a surprise to the Communist Party establishment when he took power in 2012 that several senior politburo members attempted a “soft coup”. They wanted to reign in this maverick who was threatening their comfortable status quo. They became the first targets of Xi’s aggressive ‘anti-corruption’ campaign, which has resulted in up to 100 top generals and party members being jailed. Some 2.7 million party officials have been investigated, and 1.5 million purged. “The impact of the anti-corruption campaign is much like in any political system, where you have a big clean out, or somebody cleans out tons of people, he has created enormous numbers of enemies, bad enemies,” McGregor told the Lowy Institute.

Chairman Xi now faces the classic “strongman” quandary. If he were to step down or be toppled from power, his enemies would move on him, his family and his supporters. To counter this, Xi has been building up a public image as being a “Great Helmsman”, wrapping himself in an aura of wisdom and benevolence. But, his authoritarian tendencies could cause this to backfire. “It would seem Xi has had a remarkable run. But, strangely, his actions make it appear otherwise,” writes Professor of Asia-Pacific Security Studies Bates Gill. Professor Gill details a series of recent moves which he says indicates Chairman Xi is becoming increasingly nervous including consolidating power, imposing obedience and asserting party control over the military. He has also stepped up surveillance systems, restricted the media and imprisoned hundreds of thousands of Muslim Uighurs in “re-education” camps. “He surely has much to worry about,” Professor Gill writes. “But the biggest challenge is how to continue maintaining economic growth and social stability without losing the party’s absolute political control. It’s the same challenge every Chinese leader since Deng has faced.” Professor Gill says Xi has chosen to confront his fears through tighter controls. “He clearly sees the party’s extensive system of ideology, propaganda, surveillance and control as absolutely necessary to achieve the Chinese Dream — the country’s re-emergence as a powerful, wealthy and respected great power. “Whether or not the outside world ultimately respects Xi’s autocratic approach to power and leadership, he is convinced it is best for China and, by extension, benefits the world.” Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer. Continue the conversation @JamieSeidel |