This article is more than

1 year oldNew York governor vetoes bill to make conviction challenges easier

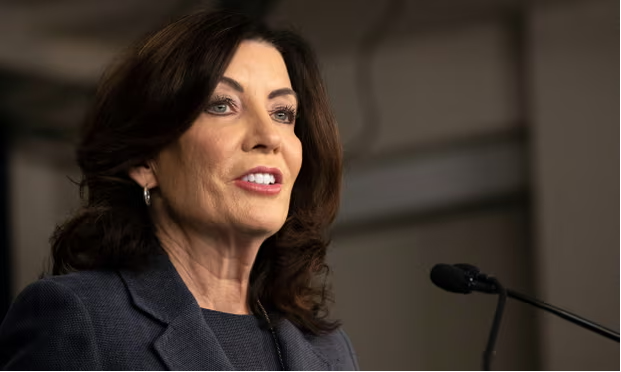

The New York governor, Kathy Hochul, vetoed a bill days before Christmas that would have made it easier for people who have pleaded guilty to crimes to challenge their convictions, a measure that was favored by criminal justice reformers but fiercely opposed by prosecutors.

The Democrat said the bill’s “sweeping expansion of eligibility for post-conviction relief” would “upend the judicial system and create an unjustifiable risk of flooding the courts with frivolous claims”, in a veto letter released on Saturday.

Under existing state law, criminal defendants who plead guilty are usually barred from trying to get their cases reopened based on a new claim of innocence, except in certain circumstances involving new DNA evidence.

The bill passed by the legislature in June would have expanded the types of evidence that could be considered proof of innocence, including video footage or evidence of someone else confessing to a crime. Arguments that a person was coerced into a false guilty plea would have also been considered.

Prosecutors and advocates for crime victims warned the bill would have opened the floodgates to endless, frivolous legal appeals by the guilty.

The Erie county district attorney, John Flynn, the president of the District Attorney’s Association of the State of New York, wrote in a letter to Hochul in July that the bill would create “an impossible burden on an already overburdened criminal justice system”.

The legislation would have benefitted people such as Reginald Cameron, who was exonerated in 2023, years after he pleaded guilty to first-degree robbery in exchange for a lesser sentence. He served more than eight years in prison after he was arrested alongside another person in 1994 in the fatal shooting of Kei Sunada, a 22-year-old Japanese immigrant. Cameron, then 19, had confessed after being questioned for several hours without attorneys.

His conviction was thrown out after prosecutors reinvestigated the case, finding inconsistencies between the facts of the crime and the confessions that were the basis for the conviction. The investigation also found the detective that had obtained Cameron’s confessions was also connected to other high-profile cases that resulted in exonerations, including the Central Park Five case.

Various states including Texas have implemented several measures over the years intended to stop wrongful convictions. Texas amended a statute in 2015 that allows a convicted person to apply for post-conviction DNA testing. In 2017, another amended rule requires law enforcement agencies to electronically record interrogations of suspects in serious felony cases in their entirety.

“We’re pretty out of step when it comes to our post-conviction statute,” Amanda Wallwin, a state policy advocate at the Innocence Project, said of New York.

“We claim to be a state that cares about racial justice, that cares about justice period. To allow Texas to outmaneuver us is and should be embarrassing,” she said.

In 2018, New York’s highest court affirmed that people who plead guilty cannot challenge their convictions unless they have DNA evidence to support their innocence. That requirement makes it very difficult for defendants to get their cases heard before a judge, even if they have powerful evidence that is not DNA-based.

Over the past three decades, the proportion of criminal cases that make it to trial in New York has steadily declined, according to a report by the New York State Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. About 99% of misdemeanor charges and 94% of felony charges in the state are resolved by guilty pleas.

“In my work, I know there there are a lot of circumstances where people plead guilty to crimes because they are advised or misadvised by their attorneys at the time,” said Donna Aldea, a lawyer at the law firm Barket Epstein Kearon Aldea & LoTurco. “Sometimes they’re afraid that if they go to trial, they’ll face much worse consequences, even if they didn’t commit the crime.”

She said the state’s criminal justice system right now is framed in a way that makes it impossible for people to challenge their guilty pleas years later when new evidence emerges, or when they are in a better financial position to challenge their convictions.

Keywords

Newer articles

<p>Chinese officials say they "firmly oppose" the platform being divested.</p>

Ukraine ‘will have a chance at victory’ with new US aid, Zelenskyy says

Congress passes bill that could ban TikTok after years of false starts

Ukraine war: Kyiv uses longer-range US missiles for first time

How soon could US ban TikTok after Congress approved bill?

TikTok faces US ban as bill set to be signed by Biden

‘LOSING CREDIBILITY’: Judge explodes at Trump lawyers as case heats up

Claim rapper ‘made staff watch her have sex’

KANYE WEST PLANS TO LAUNCH 'YEEZY PORN' ... Could Be Coming Soon!!!

Megan Thee Stallion’s Ex-Makeup Guru Talks. It’s Not Pretty.