This article is more than

5 year oldAn Alabama “ISIS Bride” Wants To Come Home. Can We Forgive Her Horrifying Social Media Posts?

I started texting with Hoda Muthana April 5, 2015, when she was 20 and I was 26.

We were talking on Kik, a messaging service mostly used by dating app users looking to hook up — and jihadis looking to communicate. Muthana’s first question was how I’d found her. “I’m a journalist,” I told her. “I do my job well.”

“No ur not,” she replied. “Don’t get a big head.”

So I proved it to her, by sending her a smiling high school graduation photograph of herself. That’s when Muthana threatened me for the first time.

“If I see that photo online. I will get someone to kill you,” she texted me back.

At the time, Muthana was a curiosity, a shy American college girl turned “ISIS bride.” Now, she’s sitting in a Kurdish refugee camp with her son, Adam, who will turn 2 soon, begging to return to her homeland, the United States. She has become a symbol of a new debate about the young people — and, in particular, the women — who were radicalized by ISIS. Are they monsters, or victims? And more broadly, in this age of online radicalization, who has traveled beyond redemption? Who can be deradicalized, and who can be redeemed?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I do know Muthana better than most of the reporters asking them. I have spent nearly four years tracking Muthana, who fled her Hoover, Alabama, home in 2014 to join ISIS in Syria, across various social media platforms and communicating with her in private messages while she was a member of the brutal terror group.

When Muthana resurfaced earlier this year in the refugee camp, telling reporters she was wrong to join ISIS and that she now wants to return, several media outlets accompanied their stories with a handful of her old tweets calling for violence against Americans.

But her social media footprint is actually more vast and troubling, and I am reporting it here for the first time, and publishing alongside this story my archive of four years of Muthana's life as she presented it on social media. I have saved posts of hers from various accounts on multiple platforms, including Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and even Ask.fm. This unfiltered glimpse into her life with ISIS shows she relentlessly pushed the terror group’s ideology and propaganda, the key to its ability to inspire violence worldwide.

With a chatty ease, Muthana tweeted for her Muslim “sisters” in the US to join her in Syria and denounced her own father on Instagram. She shared photos claiming ISIS provided her with lavish apartments and powerful weapons. She memorialized her ISIS-provided husbands, killed in battle. She praised the deaths of Americans at ISIS’s hands and encouraged vehicular attacks worldwide. She encouraged horrific attacks that have killed thousands of people around the world — including dozens in the very nation she wants to call home once again.

With each new account she created, she messaged me — and in some instances sought me out.

Even though she threatened my life in our first exchanges, and even though I never saw a social media post from her in four years where she expressed anything less than total allegiance to the so-called Islamic State, I can’t see Muthana as a one-dimensional monster. Here was a sheltered young woman who was given her first cellphone upon graduation from high school in 2013 and with it her first chance to express herself on her own terms. She soon was extremely online, using Instagram, Tumblr, Google+, the now-forgotten video app Keek, and a public Twitter account where she joked with her siblings and classmates — but not Facebook, which her father had banned his daughters from using years earlier. But then she created a Twitter account specifically for her growing participation in the Muslim “Twittersphere” — and she didn’t let her siblings follow. That account, in the year leading up to her departure, telegraphed a growing fascination and alignment with the brutal terror group’s ideology.

Like Muthana, I’m extremely online and I understand the kind of influence communities on the internet can have on people searching for purpose and connection that’s missing from their lives. And as I dove deeper into Muthana’s life, I saw her as a young woman caught between two worlds, a child of immigrants frustrated by the restrictions they placed on her and her sister while watching her brothers seemingly do whatever they pleased. A person searching for the connections that her parents’ rules made it so hard to form. A place to belong, and a greater purpose — though the one she ultimately found was utterly misguided. Her tweets were an extension of herself, performing what she perceived as the best version of herself, optimizing herself for the unforgiving seductions of social media.

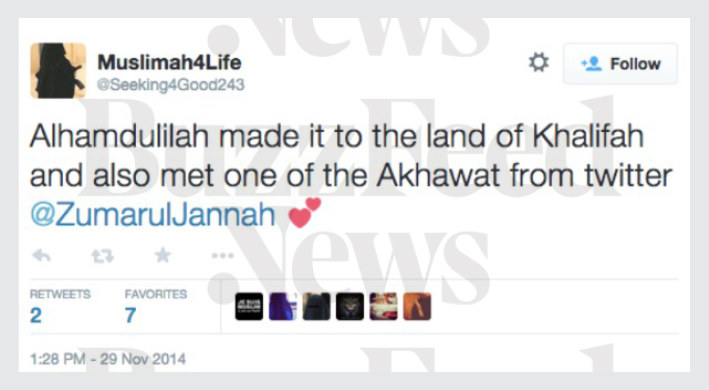

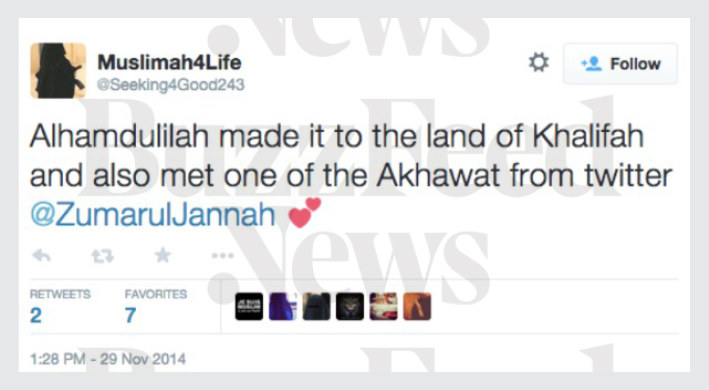

And she was seduced. In a recent interview, Muthana said that seeing a Twitter friend make it to Syria was what drove her to join ISIS. And her success inspired other women in turn. Soon after her arrival, another young woman tweeted happily that she had finally joined the terror group — and there she met Muthana, her Twitter friend:

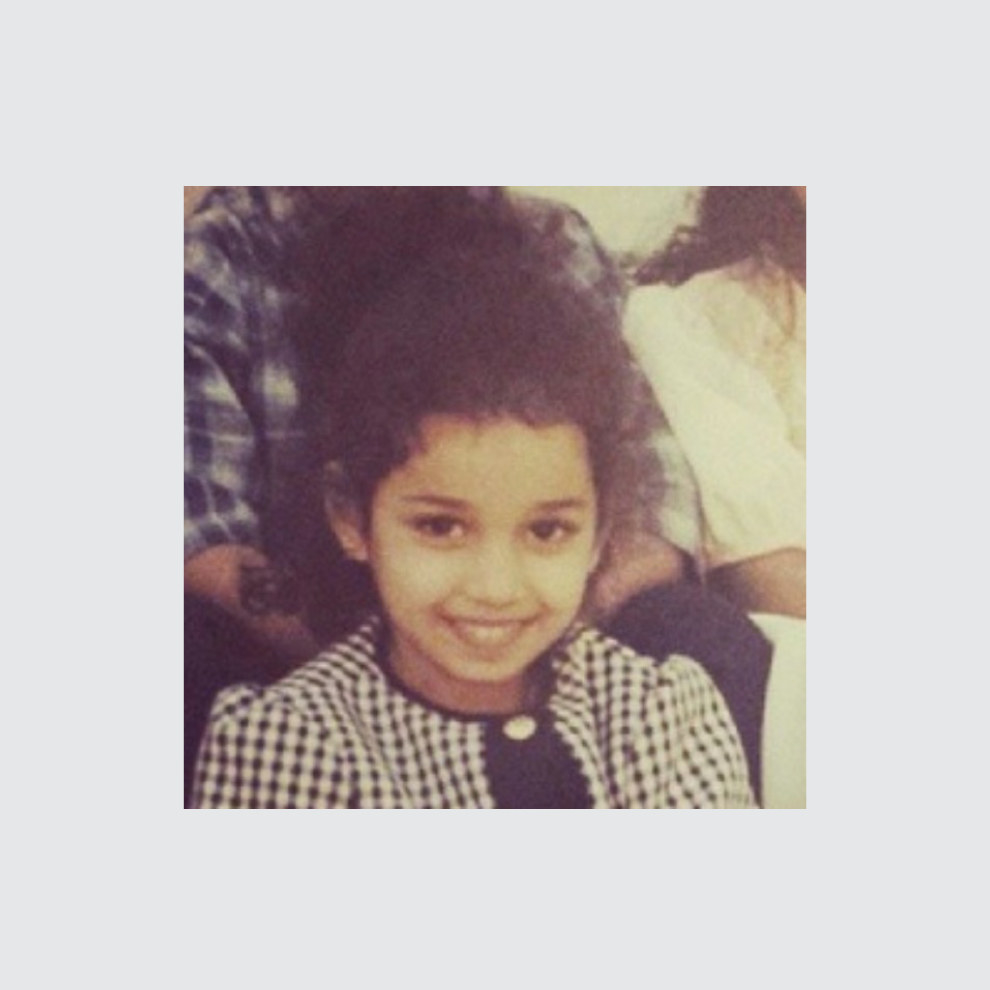

After identifying Muthana through her tweets in 2015, what solidified my interest in her story was one particular photo of her and her siblings, a #tbt post on her brother’s Instagram account. After seeing this smiling girl, I couldn’t help but have a natural curiosity about what made her the way she became.

I flew to Hoover, Alabama, attended Friday prayers at her mosque, talked to her friends, visited her college campus, and, finally, earned the trust of her father. I wrote the first in-depth profile of an American woman who joined ISIS, and sparked a firestorm of media coverage.

American citizens who left to join ISIS have been repatriated in the past. But Muthana’s current legal case is unique: The government argues she wasn’t a US citizen to begin with, and President Donald Trump named her in a tweet demanding she not be allowed back.

Muthana’s father, on behalf of his daughter and grandson, has sued the US government in a bid to bring her back, ensuring that the political and cultural battle around her will remain in the headlines. American authorities maintain that she is not and has never been a US citizen, arguing her father was still technically a Yemeni diplomat at the time of her birth, despite the fact that she was issued two American passports. Although the case is still in its early stages, the government has recently signaled that it plans to use some of her social media posts, and quotes from her 2015 interview with me, to argue that Muthana’s father has no right to represent her and that he has failed to prove that she actually wishes to come home.

Muthana’s lawyers told BuzzFeed News that her lawsuit has nothing to do with her posts, since the government’s opposition to her return is solely based on their stance that she is not a citizen. Charles Swift, the attorney representing her father in the lawsuit, added that her social media posts were made before Muthana denounced ISIS and expressed a desire to return to the US, where she understands she would likely face criminal charges and jail time.

Muthana sent her first tweet from ISIS territory shortly after arriving there. In it, she and three other new women ISIS members hold their passports from the US, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada. She wrote that they were about to burn them in a bonfire.

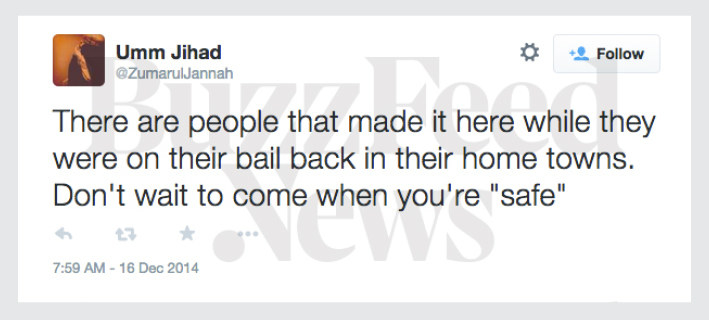

In the following weeks, Muthana began tweeting about her life and encouraged others to make the journey — which she, like many other ISIS members, referred to as a hijrah, meaning pilgrimage or immigration — and join the terror group themselves. It was a typical ISIS recruitment tactic, intended to show people they had nothing to fear.

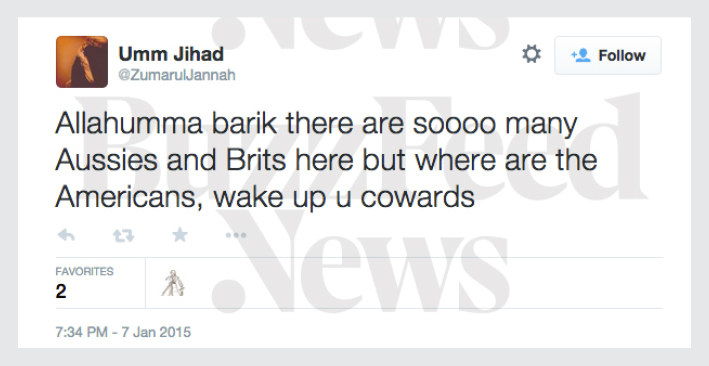

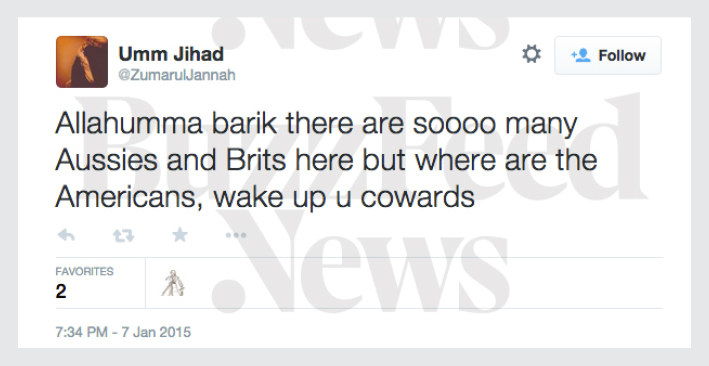

Muthana particularly encouraged other Americans to join ISIS.

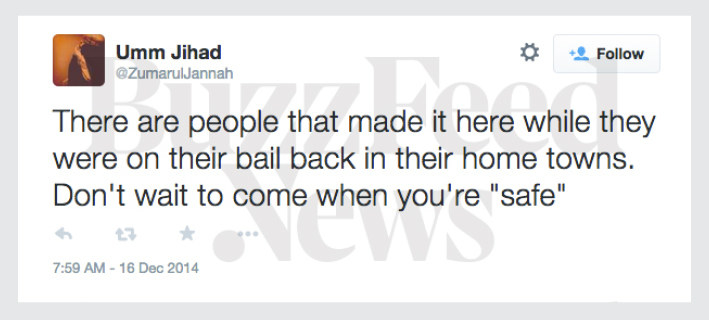

On Dec. 20, 2014 — less than a month after she arrived in Syria — Muthana married 23-year-old Suhan Rahman, an Australian known as Abu Jihad al-Australi. After her marriage, she took on the new kunya, or nom-de-guerre, “Umm Jihad” — or “Mother of jihad.”

Muthana told BuzzFeed News that Rahman was killed in battle on March 17, 2015 — they had been married for less than three months. On March 18, she tweeted a photo of her husband's corpse, glorifying his death and calling herself “content.” (BuzzFeed News has blurred the image.)

Muthana and her friend and fellow ISIS widow, Australian Zehra Duman — who, like Muthana, is now trying to return to her home country — tweeted to each other about their jealousy that their husbands were "martyred" before they were.

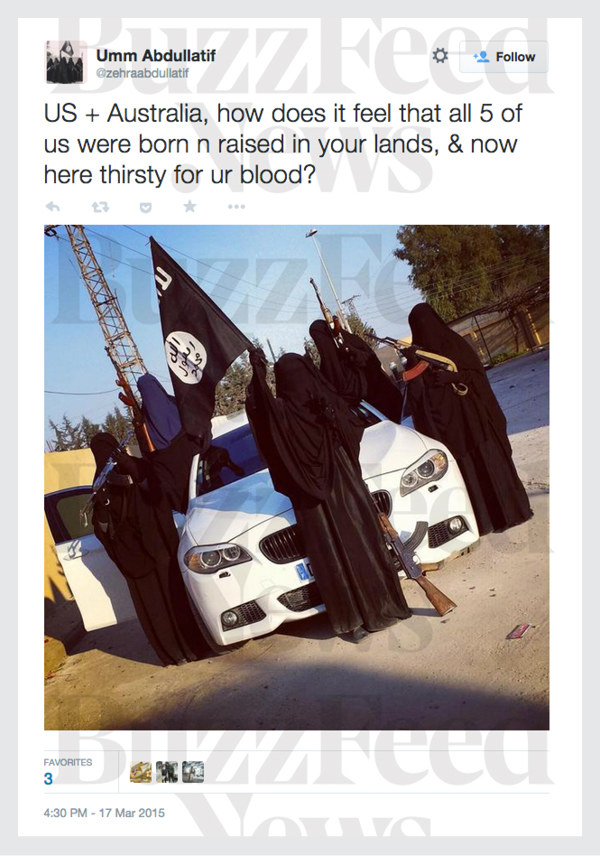

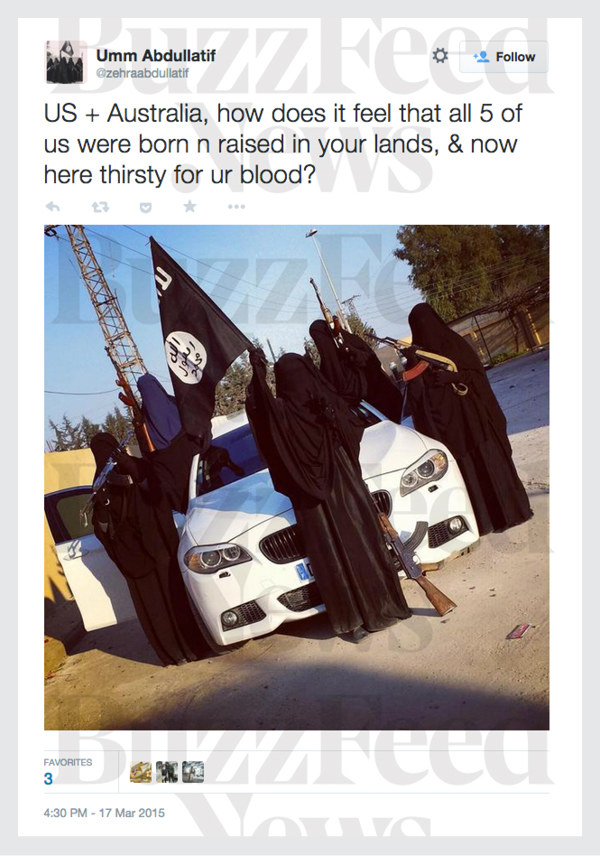

Around the same time, Duman tagged Muthana in photos posted on Twitter. Muthana confirmed to me in 2015 that she was one of the women holding rifles and, per Duman’s caption, “thirsty for blood.”

On March 19, 2015, Muthana posted a series of tweets encouraging terrorist attacks on the US that have since been quoted in stories around the world as an example of her radicalization.

In these tweets, she urged those unable to travel to ISIS-controlled territory to expand the “Khilafah,” or caliphate, in their homelands, and urged her followers to terrorize the “kuffar” — a derogatory word used by ISIS supporters to describe non-Muslims.

I started texting with Hoda Muthana April 5, 2015, when she was 20 and I was 26.

We were talking on Kik, a messaging service mostly used by dating app users looking to hook up — and jihadis looking to communicate. Muthana’s first question was how I’d found her. “I’m a journalist,” I told her. “I do my job well.”

“No ur not,” she replied. “Don’t get a big head.”

So I proved it to her, by sending her a smiling high school graduation photograph of herself. That’s when Muthana threatened me for the first time.

“If I see that photo online. I will get someone to kill you,” she texted me back.

At the time, Muthana was a curiosity, a shy American college girl turned “ISIS bride.” Now, she’s sitting in a Kurdish refugee camp with her son, Adam, who will turn 2 soon, begging to return to her homeland, the United States. She has become a symbol of a new debate about the young people — and, in particular, the women — who were radicalized by ISIS. Are they monsters, or victims? And more broadly, in this age of online radicalization, who has traveled beyond redemption? Who can be deradicalized, and who can be redeemed?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I do know Muthana better than most of the reporters asking them. I have spent nearly four years tracking Muthana, who fled her Hoover, Alabama, home in 2014 to join ISIS in Syria, across various social media platforms and communicating with her in private messages while she was a member of the brutal terror group.

When Muthana resurfaced earlier this year in the refugee camp, telling reporters she was wrong to join ISIS and that she now wants to return, several media outlets accompanied their stories with a handful of her old tweets calling for violence against Americans.

But her social media footprint is actually more vast and troubling, and I am reporting it here for the first time, and publishing alongside this story my archive of four years of Muthana's life as she presented it on social media. I have saved posts of hers from various accounts on multiple platforms, including Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and even Ask.fm. This unfiltered glimpse into her life with ISIS shows she relentlessly pushed the terror group’s ideology and propaganda, the key to its ability to inspire violence worldwide.

With a chatty ease, Muthana tweeted for her Muslim “sisters” in the US to join her in Syria and denounced her own father on Instagram. She shared photos claiming ISIS provided her with lavish apartments and powerful weapons. She memorialized her ISIS-provided husbands, killed in battle. She praised the deaths of Americans at ISIS’s hands and encouraged vehicular attacks worldwide. She encouraged horrific attacks that have killed thousands of people around the world — including dozens in the very nation she wants to call home once again.

With each new account she created, she messaged me — and in some instances sought me out.

Even though she threatened my life in our first exchanges, and even though I never saw a social media post from her in four years where she expressed anything less than total allegiance to the so-called Islamic State, I can’t see Muthana as a one-dimensional monster. Here was a sheltered young woman who was given her first cellphone upon graduation from high school in 2013 and with it her first chance to express herself on her own terms. She soon was extremely online, using Instagram, Tumblr, Google+, the now-forgotten video app Keek, and a public Twitter account where she joked with her siblings and classmates — but not Facebook, which her father had banned his daughters from using years earlier. But then she created a Twitter account specifically for her growing participation in the Muslim “Twittersphere” — and she didn’t let her siblings follow. That account, in the year leading up to her departure, telegraphed a growing fascination and alignment with the brutal terror group’s ideology.

Like Muthana, I’m extremely online and I understand the kind of influence communities on the internet can have on people searching for purpose and connection that’s missing from their lives. And as I dove deeper into Muthana’s life, I saw her as a young woman caught between two worlds, a child of immigrants frustrated by the restrictions they placed on her and her sister while watching her brothers seemingly do whatever they pleased. A person searching for the connections that her parents’ rules made it so hard to form. A place to belong, and a greater purpose — though the one she ultimately found was utterly misguided. Her tweets were an extension of herself, performing what she perceived as the best version of herself, optimizing herself for the unforgiving seductions of social media.

And she was seduced. In a recent interview, Muthana said that seeing a Twitter friend make it to Syria was what drove her to join ISIS. And her success inspired other women in turn. Soon after her arrival, another young woman tweeted happily that she had finally joined the terror group — and there she met Muthana, her Twitter friend:

After identifying Muthana through her tweets in 2015, what solidified my interest in her story was one particular photo of her and her siblings, a #tbt post on her brother’s Instagram account. After seeing this smiling girl, I couldn’t help but have a natural curiosity about what made her the way she became.

I flew to Hoover, Alabama, attended Friday prayers at her mosque, talked to her friends, visited her college campus, and, finally, earned the trust of her father. I wrote the first in-depth profile of an American woman who joined ISIS, and sparked a firestorm of media coverage.

American citizens who left to join ISIS have been repatriated in the past. But Muthana’s current legal case is unique: The government argues she wasn’t a US citizen to begin with, and President Donald Trump named her in a tweet demanding she not be allowed back.

Muthana’s father, on behalf of his daughter and grandson, has sued the US government in a bid to bring her back, ensuring that the political and cultural battle around her will remain in the headlines. American authorities maintain that she is not and has never been a US citizen, arguing her father was still technically a Yemeni diplomat at the time of her birth, despite the fact that she was issued two American passports. Although the case is still in its early stages, the government has recently signaled that it plans to use some of her social media posts, and quotes from her 2015 interview with me, to argue that Muthana’s father has no right to represent her and that he has failed to prove that she actually wishes to come home.

Muthana’s lawyers told BuzzFeed News that her lawsuit has nothing to do with her posts, since the government’s opposition to her return is solely based on their stance that she is not a citizen. Charles Swift, the attorney representing her father in the lawsuit, added that her social media posts were made before Muthana denounced ISIS and expressed a desire to return to the US, where she understands she would likely face criminal charges and jail time.

Muthana sent her first tweet from ISIS territory shortly after arriving there. In it, she and three other new women ISIS members hold their passports from the US, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada. She wrote that they were about to burn them in a bonfire.

In the following weeks, Muthana began tweeting about her life and encouraged others to make the journey — which she, like many other ISIS members, referred to as a hijrah, meaning pilgrimage or immigration — and join the terror group themselves. It was a typical ISIS recruitment tactic, intended to show people they had nothing to fear.

Muthana particularly encouraged other Americans to join ISIS.

On Dec. 20, 2014 — less than a month after she arrived in Syria — Muthana married 23-year-old Suhan Rahman, an Australian known as Abu Jihad al-Australi. After her marriage, she took on the new kunya, or nom-de-guerre, “Umm Jihad” — or “Mother of jihad.”

Muthana told BuzzFeed News that Rahman was killed in battle on March 17, 2015 — they had been married for less than three months. On March 18, she tweeted a photo of her husband's corpse, glorifying his death and calling herself “content.” (BuzzFeed News has blurred the image.)

Muthana and her friend and fellow ISIS widow, Australian Zehra Duman — who, like Muthana, is now trying to return to her home country — tweeted to each other about their jealousy that their husbands were "martyred" before they were.

Around the same time, Duman tagged Muthana in photos posted on Twitter. Muthana confirmed to me in 2015 that she was one of the women holding rifles and, per Duman’s caption, “thirsty for blood.”

On March 19, 2015, Muthana posted a series of tweets encouraging terrorist attacks on the US that have since been quoted in stories around the world as an example of her radicalization.

In these tweets, she urged those unable to travel to ISIS-controlled territory to expand the “Khilafah,” or caliphate, in their homelands, and urged her followers to terrorize the “kuffar” — a derogatory word used by ISIS supporters to describe non-Muslims.

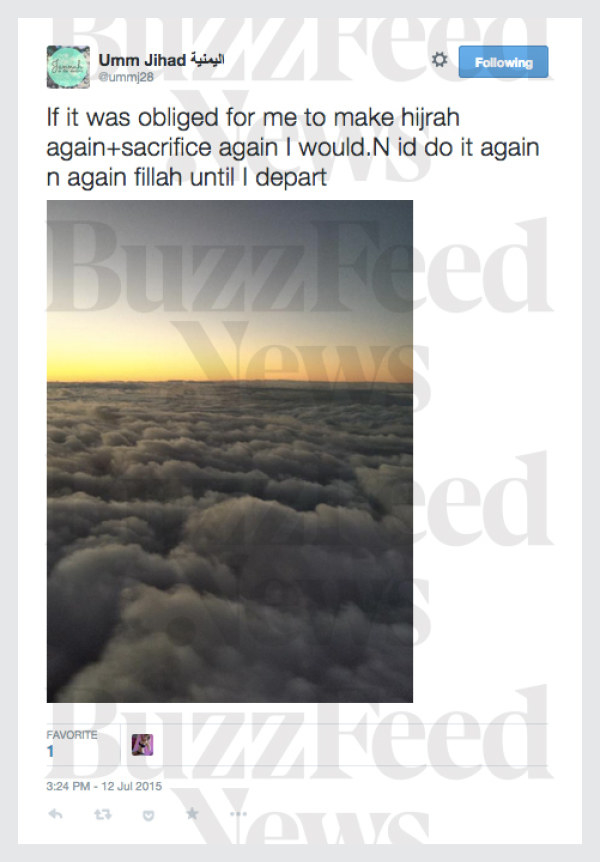

On July 12, she tweeted a photo of the view from an airplane window, likely taken on her journey from the US to join ISIS in November 2014. She continued her call for others to join ISIS and reiterated her decision to join the group: “id do it again.”

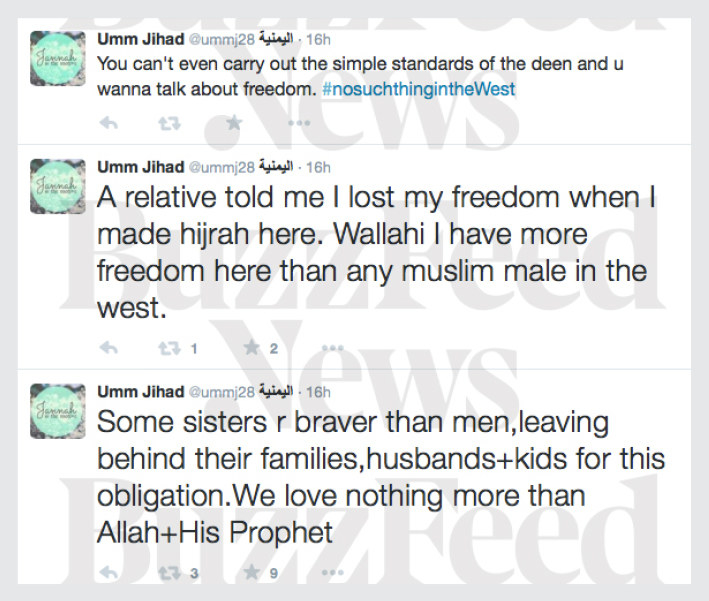

She followed with a longer defense of her decision to join ISIS, writing, “I have more freedom here than any muslim male in the west,” and saying women who made the journey were brave.

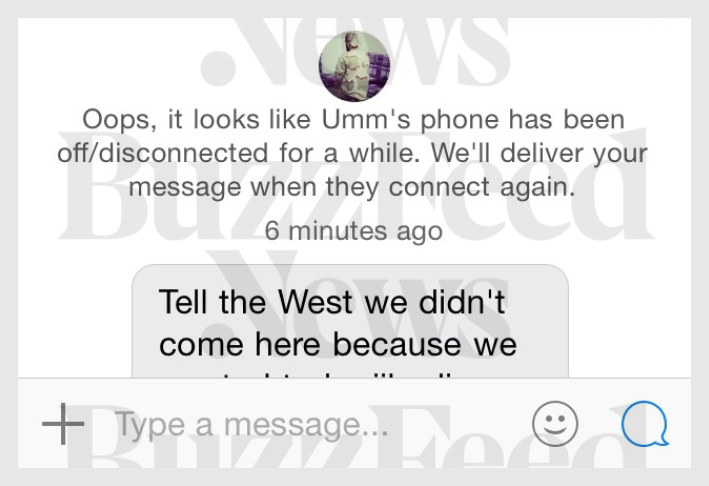

On July 18, she contacted me on Kik and asked me to convey a message “to the West.” Her unprompted communication came during a time when stories about so-called jihadi brides were grabbing global news headlines. For years, sensationalist stories in this vein have depicted the women as empty-headed teenagers who joined ISIS so they could marry handsome fighters. This inaccurate narrative removes the agency from these women who knowingly joined a terrorist organization and diminishes their involvement in the group’s activities — something that ISIS victims are now highlighting as Muthana and other “ISIS brides” are trying to return home.

Here’s what she wrote:

Tell the West we didn't come here because we wanted to be jihadi wives. If that were the case you'd see most of us trying to go back.

Who would risk everything they know and own to have a marriage thats span isn't guaranteed for the next day. And if one came for marriage then in that i still say there is nothing wrong in it for muslim women should refrain in marrying men who are not in jihad or support it.

We came because it's an obligation upon us upon every muslim to unite under one Khilafah, we came because it's impermissible for us to live under the laws of man, we came so we can live under justice ie. Shar'iah law.

We came because one day when we charge into the West we won't be affected like those who have remained behind by choice with the polytheist. As Rasulullah [peace be upon him] said, he isn't responsible for those who remain with the polytheist.

This isn't a joke like the West like to portray it, they like to deem all of us here as social outcast and infer that everyone here isn't normal. This is normal, this is real, this is the malahim and it will happen whether they like it or not because Allah had promised us.

Following this lengthy communication, Muthana and I exchanged messages about the way ISIS women were depicted in the media as opposed to male members of the group. I referred to it as sexist, and she agreed.

A month later, Muthana and a friend created a new Twitter account and posted messages laying out a forceful defense of ISIS and criticizing those who denounced the group for their acts of violence. Using the group’s warped interpretation of Islam, she claimed that beheading people and burning them alive was encouraged by the faith and that people shouldn’t turn away from ISIS because “we beheaded a former US soldier who was apparently an aid worker” — likely Peter Kassig.

She also, ironically, admonished some of her peers for showing “sympathy to these journalists.”

Using this new account, Muthana once again encouraged Americans to kill Obama.

I came across this Twitter account after I had made the mistake of tweeting that Muthana had run away from home at 19 when she was, in fact, 20. I got the below response, typical of Muthana’s tendency to follow my social media even when I didn’t know it was her. It didn’t seem like anyone else was in control of the account.

Although Muthana criticized me for getting her age wrong in this tweet four years ago, she is now telling reporters — and it is being widely and inaccurately reported — that she was 19 when she left the US.

This account was removed from the platform soon after she and I exchanged messages on Sept. 3, 2015. It would be approximately a year and a half before I found her on social media again.

Although she was not active on any social media profiles I was aware of for the length of 2016, Muthana and I exchanged messages on Kik throughout that year. I reached out to her about possibly doing a follow-up article, but she wouldn’t cooperate. I also reached out to her to wish her well on the major Muslim holidays.

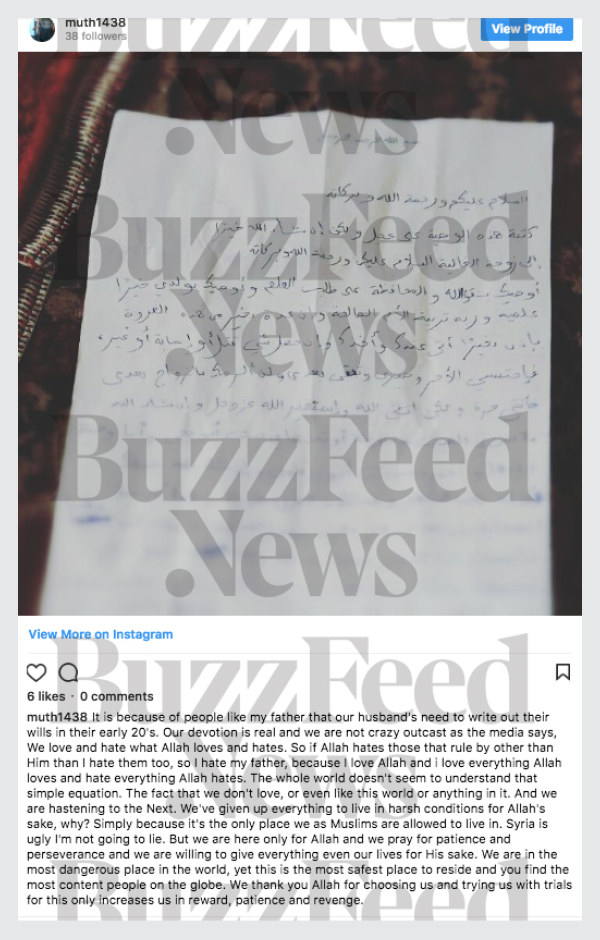

I didn't hear from her again until March 2017, when she created another Instagram account, @muth1438, and tagged me in the comments of a vitriolic post about her father — the same person currently fighting to bring her and her son, with whom she was pregnant at the time of the post, back to the US.

On March 15, she posted a lengthy message showing what she said was her second husband's handwritten last will and testament. In the recent interview with the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism, Muthana identified her second husband as a 19-year-old Tunisian named Osama Ziad, who she said was not a fighter but a scholar who worked in a “shariah academy of sorts.”

Based on the timeline that Muthana gave the ICSVE, her second husband was already dead when she made this first post. She said that in February, when she was six months pregnant, he left her at a friend’s house and never returned. He had volunteered to fight with the intention of dying in battle without telling her, planning to leave her alone with his unborn child. When she posted a picture of what she said was her late husband’s will to Instagram, she was seven months pregnant; her husband's will included instructions in Arabic for her to take care of his son.

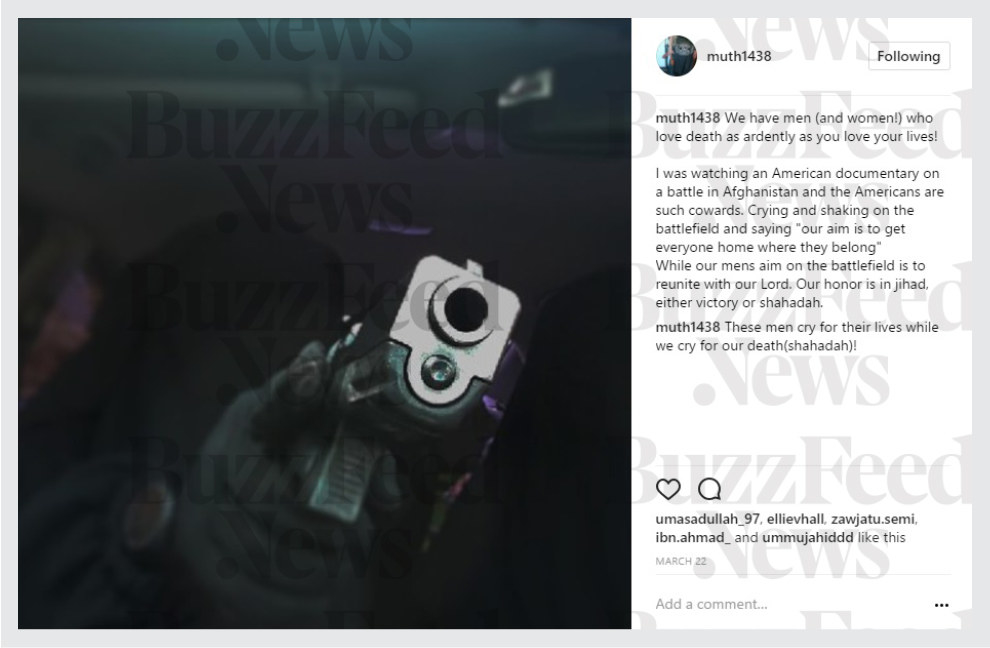

A week later, she posted an image of a handgun pointed at a camera along with a caption about how she “was watching an American documentary on a battle in Afghanistan.” She called American soldiers “cowards” and praised ISIS soldiers as brave. Her spreading of ISIS’s message showed no signs of abating at this point.

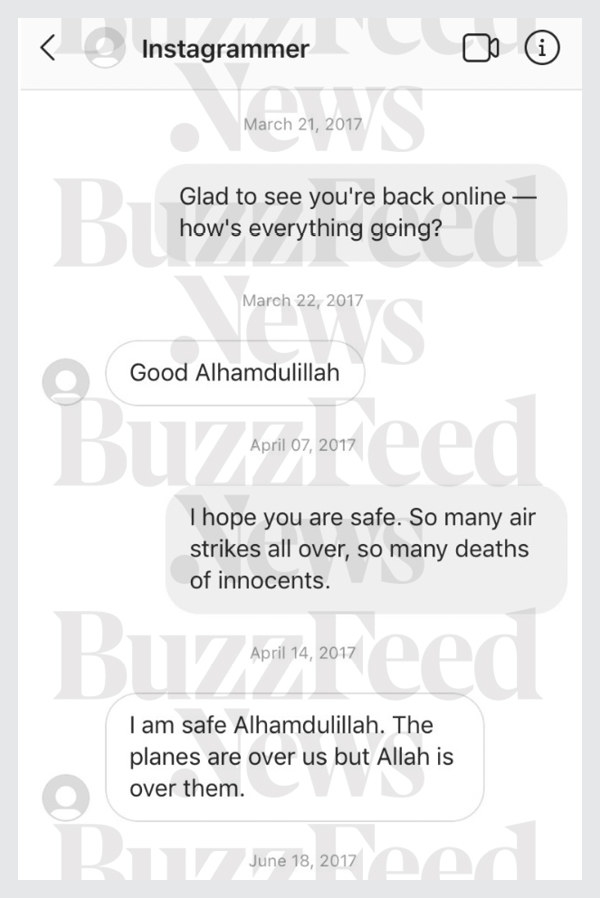

The day she posted this anti-American message on Instagram, Muthana replied to the direct message I’d sent when she resurfaced online. I messaged her again in April as conditions were rapidly deteriorating in Syria.

(The screenshot above was retrieved after Muthana’s Instagram account was removed from the platform.)

Muthana continued to be active on Instagram over the next few months, and posted an image of a chocolate cake on May 1, 2017 — 18 days before she gave birth to her son, court records indicate.

She continued to post militant images and anecdotes from her life in ISIS for the two months following her son's birth.

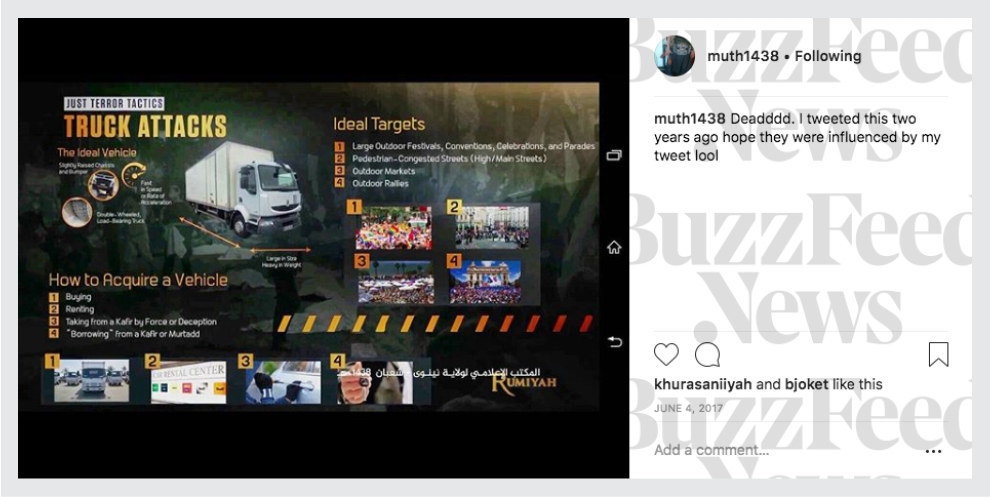

On June 4, she tweeted an image from the ISIS propaganda magazine Dabiq about vehicular attacks — and wrote that she hoped her tweets from 2015 on the topic had inspired similar attacks.

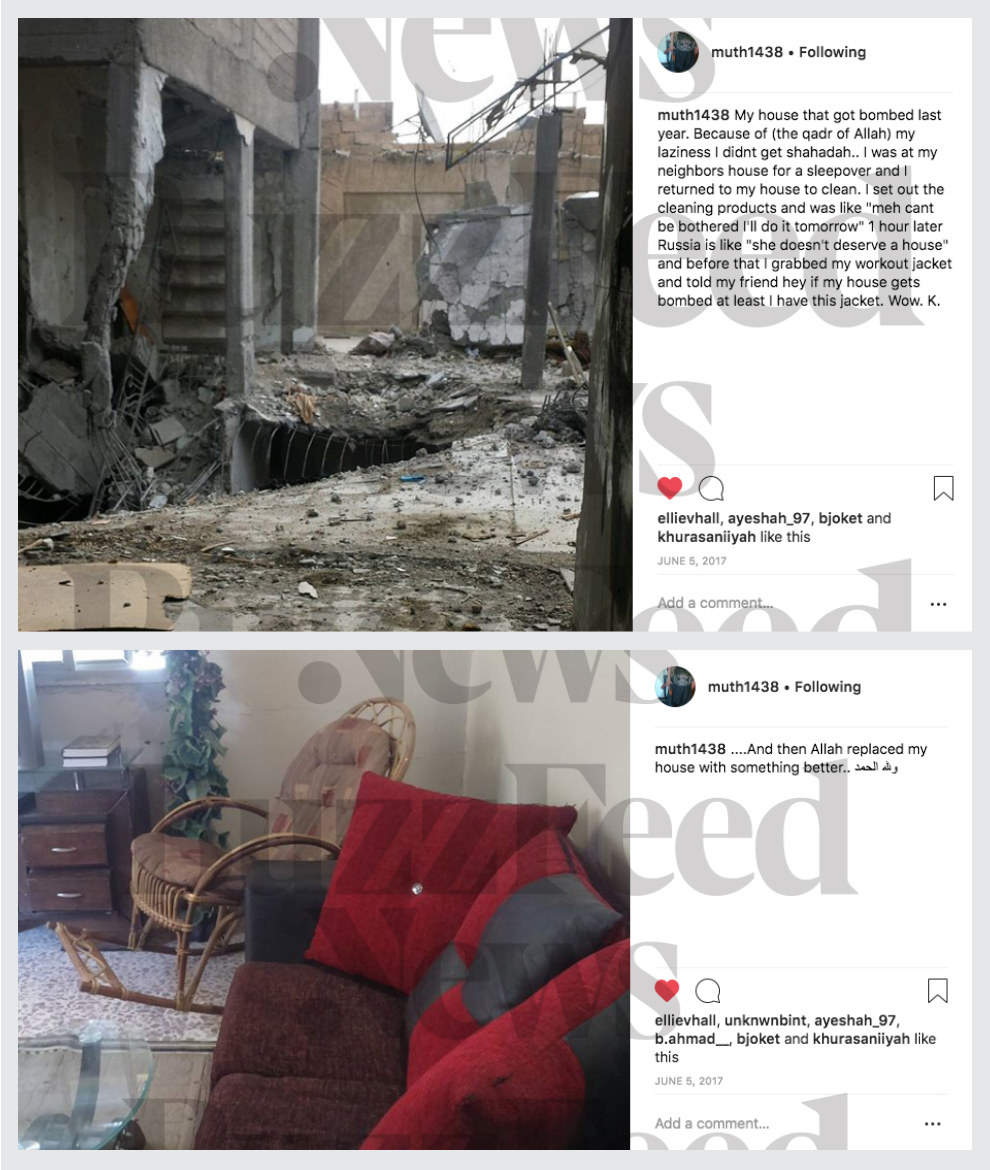

She followed this post with what she said was an image of her home destroyed in an airstrike, and a picture of the new residence. “Allah replaced my house with something better,” she wrote, perpetuating the idea — that she’d rescind in later interviews — that ISIS cares for its community.

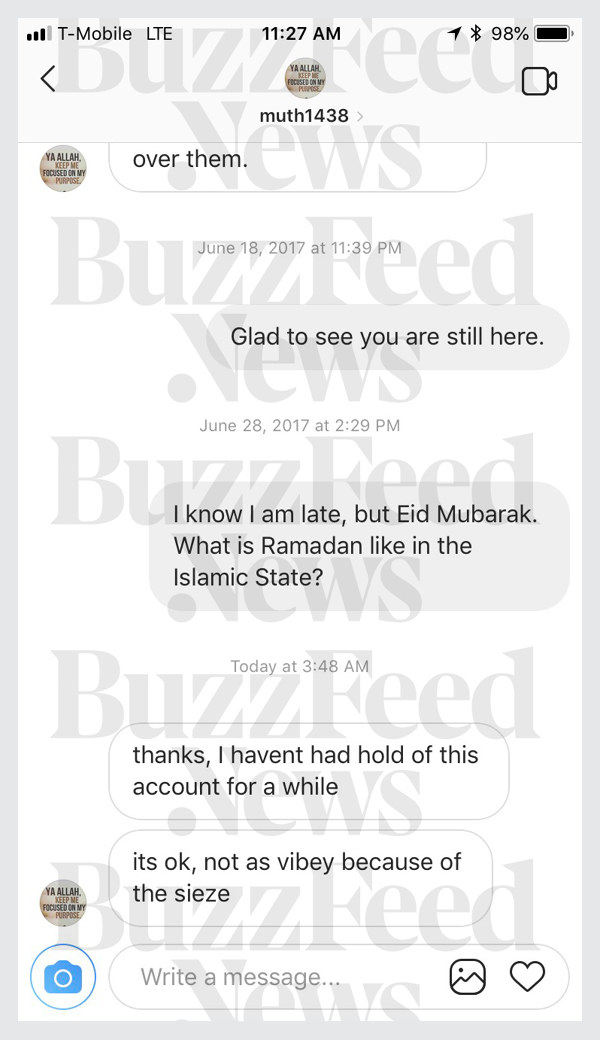

Muthana's Instagram account remained up — but not updated — for a year. The last image posted was dated June 9, 2017. I reached out to her to wish her well on Eid, the Muslim holiday celebrated at the end of Ramadan. I would not hear back or see her online again for 15 months.

Then, on Sept. 25, 2018, I received an Instagram message from Muthana’s account in response to the question I had asked her more than a year ago. She wrote that she didn’t have control of the account for a while but had regained the login.

At this point, it is impossible to know whether it was truly Muthana who sent me this message. It seems plausible that she may have had access to a phone and therefore her Instagram account — court records state that she fled ISIS in December 2018 after “several months of looking for opportunities." But given the deteriorating situation in Syria, I was suspicious of the nonchalance of the message.

In Muthana's first interview after fleeing ISIS, she told the Guardian that she remained a zealot until 2016. She also said that her social media accounts were taken over by others. This might be true of the September 2018 message. However, I believe she was in control of her account for all of her posts in 2017.

The tone of her 2017 captions, as well as the variety of images she posted of her father and the vitriol toward him, offer a lot of proof to me that it was actually her. The way she talked about her father echoed some of the things she had said to me about her family during my interview with her over Kik in 2015. The fact that she tagged me in one of her first posts also leads me to this conclusion — she regularly reached out to me when she would resurface online.

The message in September 2018 was my last communication with Muthana — or, to be precise in this instance, an account that had once been used by Muthana — and as the year came to a close, ISIS continued to lose the last of its strongholds. She fled, and on Dec. 16, Kurdish forces took her and her son into custody.

When I was in Alabama, in 2015, I tried to walk in Muthana’s footsteps and learn what might have led her to this decision. What I found was that Muthana had removed herself from her IRL community and had been pulled into her online community — at first the Muslim "Twittersphere," as she called it, and then, slowly, the networks of women ISIS members. On the ground in Alabama, I was following a ghost. She told me that she purposefully removed herself from her community once she had the clandestine agency to establish a social media presence. At first, it was one that included her siblings, her acquaintances from the mosque, her school friends — and those who knew her in real life and on social media told me that she purposefully created a “better” version of herself for Twitter, one that gained thousands of followers. Then that version of herself connected with radicals — and slowly began to share their way of thinking.

“Have you been brainwashed?” I would ask Muthana over Kik in 2015 after she fled to Syria. She would vehemently deny it.

Why did Muthana initiate contact with me so many times, over a period of years? Why did she want me to see those moments from her life she shared on social media, particularly when it became obvious that I wasn’t going to write a story about every little thing that she did or every message she wanted to convey?

I have no answer, and given the uncertainty of Muthana’s situation, I’m not sure whether I’ll ever get one. But I do have a guess. I never lied to Muthana or attempted to bullshit her. So maybe, even when she was still posting that she wanted to live and die in ISIS, she wanted to make sure that someone would see her words and photos, to make a record of her life — and I was someone who might do an acceptable job.

Throughout the years I communicated with Muthana, I’ve expressed wishes for her safety and have told her I was happy to see that she was still alive whenever she resurfaced online. I’m sure that some people will criticize the nature of my communications with her, just as I was — wrongly, in my opinion — criticized online for writing a "sympathetic" profile of Muthana and her family.

I worried about Muthana because, on some level, I understood what it means to be a young woman who sought out a greater purpose online — albeit Muthana did so in the wrong places. While I am not Muslim, I am a practicing Catholic who attended a Catholic university, and I know what it feels like to be part of a community rooted in the shared faith that makes all believers family, and the warmth of that embrace. But I also grappled with her monstrous posts, displayed above, showing she’d become an instrument of global terrorism. I saw the pain that she caused her family whenever I would check in with her father in the months and years after the profile I wrote was published.

So when she would reappear online and make contact, when my phone would ding for the first time in months, my messages to her struck a tone of hope — that I would one day write stories about Muthana returning to the US to face charges instead of write about her and her child dying by starvation, or airstrike, or murder at the hands of the group she had once so willingly joined.

Newer articles